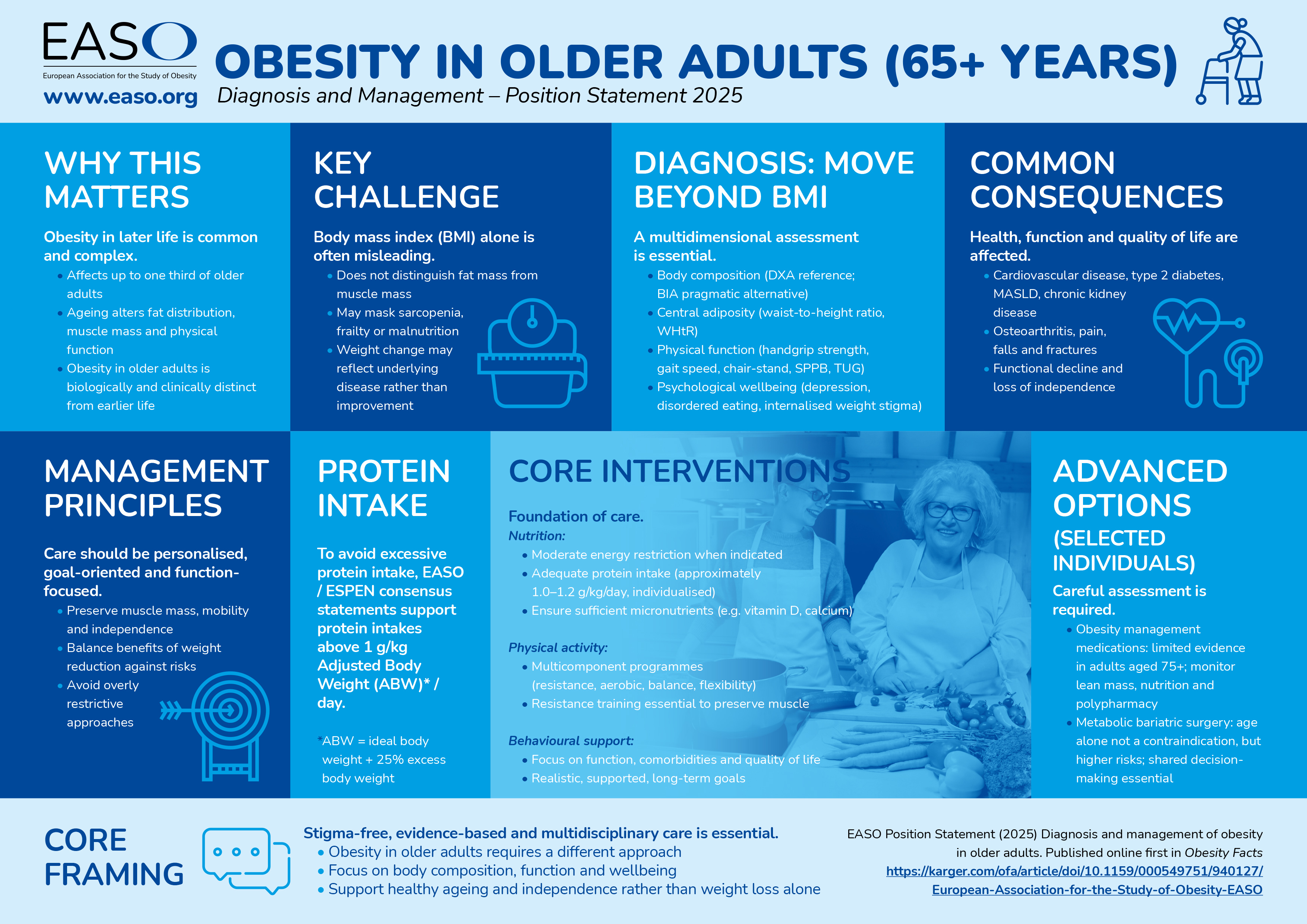

Obesity in later life is common, complex and often misunderstood. Up to one third of adults aged 65 years and over are affected, yet ageing brings biological changes that make obesity in older adults distinct from obesity earlier in life.

Changes in fat distribution, loss of muscle mass and declining physical function mean that traditional measures such as body mass index (BMI) can be misleading, masking sarcopenia, frailty or even malnutrition. Recognising this, the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) has published a position statement calling for a more nuanced, multidimensional approach to diagnosis and care in older adults living with obesity.

The new EASO Position Statement emphasises moving beyond BMI to assess body composition, central adiposity, physical function and psychological wellbeing, and to focus clinical management on preserving muscle mass, mobility, independence and quality of life. Obesity care should be personalised, goal-oriented and stigma-free, balancing potential benefits of weight reduction against risks such as functional decline. Appropriate medical nutrition therapy, multicomponent physical activity and behavioural support remain the foundation of care, with medications and metabolic bariatric surgery considered carefully in selected individuals.

The message of the authors is clear: supporting healthy ageing means prioritising function, wellbeing and independence, not weight loss alone.

The full publication is available here: https://karger.com/ofa/article/doi/10.1159/000549751/940127/European-Association-for-the-Study-of-Obesity-EASO

Interview with Professor Lorenzo M Donini, MD

We have had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Lorenzo M Donini, MD, Sapienza University of Rome, Experimental Medicine Department, who is also Co-Chair of the EASO Sarcopenic Obesity and Obesity in Older Adults Working Group, and corresponding author of the new publication. The position statement represents an important contribution to the field.

Professor Donini, what do you see as the primary drivers of the geographical and sex-based differences in obesity prevalence among older adults?

Geographical differences in obesity prevalence in older adults are mainly driven by the differences in longevity, mortality, and birth rates in the different countries. Longevity/mortality also influences the differences in obesity prevalence between males and females at older ages.

Could you elaborate on the relative contributions of age-related hormonal changes, lifestyle factors, and polypharmacy to the development of sarcopenic obesity?

Sarcopenic obesity has a multifactorial aetiology: 1) obesity can independently lead to muscle loss and function due to the negative impact of adipose tissue-dependent metabolic derangements, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance; 2) hormonal changes play a significant role in the pathogenesis of sarcopenic obesity: in women menopause is characterised by an abrupt decline in estrogen, while in men, late-onset hypogonadism reflects the progressive reduction of testosterone levels; 3) the ageing process is also associated with decreased secretion of adrenal androgens and reduced growth hormone/IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) activity.

In routine clinical practice, which methods of body composition assessment offer the best balance of accuracy, feasibility, and cost?

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is widely regarded as the reference standard for both clinical practice and research. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) represents a practical, non-invasive, and cost-effective alternative that estimates body composition based on the electrical conductivity of different human tissues.

How should clinicians integrate assessments of psychological status and functional performance into standard care pathways for older adults living with obesity?

Muscle strength (e.g. hand-grip strength) should be considered the functional parameter of choice for obesity-related assessments. Gait speed, typically assessed over a short walking distance, serves as another reliable and easily implementable measure of physical performance. For a more comprehensive performance evaluation, tools like the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) and the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test that integrate multiple components of physical performance, including balance, strength, and mobility, may be considered.

Psychological assessment in older adults with obesity should first include screening for eating behaviour disturbances (e.g. Sick Control One Fat Food (SCOFF) questionnaire). Those who screen positive should undergo further evaluation using validated tools (e.g. Eating Disorder Examination questionnaire (EDEq), . Binge Eating Scale (BES).

Thank you, very helpful. In multimodal interventions, how do you recommend that clinical professionals balance energy restriction with the need to preserve muscle mass and functional capacity?

Overly restrictive regimens may induce or exacerbate sarcopenia, micronutrient deficiencies, and frailty. Moderate energy restriction, typically around 500 kcal/day below estimated requirements, is recommended, in combination with adequate protein intake to mitigate loss of skeletal muscle mass, and appropriate essential micronutrient intake. To avoid excessive protein intake, consensus and position papers (e.g. the ones from ESPEN and EASO) have supported protein intakes above 1 g/kg adjusted body weight (ABW)·day (ABW= ideal body weight + 25% excess body weight)

Thank you for highlighting this very important issue. Regarding physical activity and exercise training, what is the optimal structure and approach of multicomponent exercise programmes for older adults? Is it still appropriate to rely on the EASO exercise training recommendations: https://easo.org/important-new-recommendations-on-exercise-training-in-the-management-of-overweight-and-obesity-in-adults/ to help support management of overweight and obesity in adults, and can contribute to health benefits beyond “scale victories”?

Multicomponent training combining flexibility, balance, aerobic (150 to 200 min/week at moderate intensity), and resistance training is strongly advised.

We can rely on the EASO exercise training recommendations (https://easo.org/important-new-recommendations-on-exercise-training-in-the-management-of-overweight-and-obesity-in-adults/) to help support management of overweight and obesity in adults. Exercise programs in older adults should, however, be tailored to individual capacities, following the FITT principle, which considers frequency, intensity, time, and type, acting synergistically with dietary protocols to promote weight loss, prevent weight regain, and reduce obesity-related complications.

What evidence supports the use of obesity-management medications in older adults, and what safety considerations should clinicians bear in mind?

Recent progress in obesity pharmacotherapy, particularly with the advent of second-generation agents, has been described as a paradigm shift in the medical management of obesity. No contraindications are present in the literature suggesting avoiding their use in older adults. However, in these subjects, gastrointestinal adverse events and lean mass reduction should be carefully verified. A tailored, individualized approach to prescribing obesity pharmacotherapy for older people is required, with careful consideration of potential risks and benefits, followed by close medical supervision

How should clinicians assess suitability for metabolic bariatric surgery in older adults, particularly in the context of frailty, sarcopenia, and multimorbidity?

Age, per se, is not an absolute contraindication to bariatric surgery. Metabolic bariatric surgery may be considered in selected patients, with attention to age-related risks, adverse effects, and long-term adherence to dietary advice.

Are outcomes post metabolic bariatric surgery comparable between older and younger adults, and where are the key gaps in evidence?

Older patients show higher odds of in-hospital mortality after bariatric surgery compared with younger adults and are at increased risk of respiratory and infectious diseases.

How should preservation of muscle mass, functional capacity, and quality of life be prioritised and measured in clinical trials and routine care?

These aspects should be considered in the first evaluation of older adults with obesity and controlled during the entire follow-up.

A multidimensional approach to older adults with obesity is mandatory (during the clinical-functional-psychological assessment, the therapeutic prescription, and the follow-up) to better take into account the heterogeneity of this age class.

The full publication is available here: https://karger.com/ofa/article/doi/10.1159/000549751/940127/European-Association-for-the-Study-of-Obesity-EASO

The Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Sarcopenic Obesity: ESPEN and EASO Consensus Statement is available here:

https://karger.com/ofa/article/15/3/321/825712/Definition-and-Diagnostic-Criteria-for-Sarcopenic